Silloth is the creation, as it were, of yesterday. But a very short time ago, the kine browsed on the greensward and the rabbit burrowed in the hills of sand, where now stand streets of well-built houses and rows of pretty villas, offering to visitors and persons in search of relaxation all the luxuries of a sea-side resort. The salubrity of its climate, good bathing, and pleasant surroundings, make it the resort of numerous visitors, who come to recruit health or are on pleasure bent.

Silloth is the creation, as it were, of yesterday. But a very short time ago, the kine browsed on the greensward and the rabbit burrowed in the hills of sand, where now stand streets of well-built houses and rows of pretty villas, offering to visitors and persons in search of relaxation all the luxuries of a sea-side resort. The salubrity of its climate, good bathing, and pleasant surroundings, make it the resort of numerous visitors, who come to recruit health or are on pleasure bent.

Bulmer’s Directory of Cumberland (1901) was fulsome in its praise, and it was not alone in proclaiming the "salubrity of the climate", with a mean average temperature not greatly different from Cornwall or Devon, with a lack of rainfall that "few places in the kingdom" could rival, and with an air "always highly charged with ozone… regarded as the health-giving and vitalising principle of the atmosphere". The theme was taken up in brochures and publicity leaflets, an Official Guide in the 1930s advising that "the nearness of the mountains and the close approach of the Gulf Stream to Silloth combine to make its atmosphere genial and mildly invigorating [and] its climate akin to that of Jersey in many respects". Comparisons were also made with Ostend and Deauville, which shared its west by north-west aspect, while a Dr Graham, who had just retired to the town, drew attention to the "emanation of free Iodine from the sea shore, a vital essential"; a Dr Rogerson, from Lockerbie, remarked that the air had "a purity and rareness and refinement nowhere else to be found on the shores of Britain, the chemical health-giving properties being so minute that they are easily assimilated by the blood and so permeate the capillary circulation"; while Dr Diggle noted that “the tides flow into the Solway Firth and remain for some hours on the sands, and then they flow out", but since he was merely a Bishop, and so (one presumes) a doctor of theology rather than of medicine, we can perhaps forgive this somewhat simplistic scientific analysis. He was, in any case, all in favour of ozone.

All this was very well, and most visitors to Silloth do indeed find the climate an unusually pleasant one for so northern a town, but its raison d’etre was as a commercial town, a port. Its story, indeed, begins further north, at Fisher’s Cross, on the northern shore of the Solway coast, near the end of Hadrian’s Wall, whose course can be seen running through the backing map. A port was developed in the 1820s, linked to Carlisle by the Carlisle Navigation Canal, leading the hamlet to be renamed Port Carlisle. The canal was initially planned as part of a grandiose west-east project, and in 1808 Thomas Telford had suggested locks wide enough to take sea-going vessels. The eventual canal was 11.25 miles long, with locks a creditable 18ft 3in wide, and Thomas Ferrier, brought in from the Forth & Clyde Canal as overseer of works, acted as engineer. It opened in 1823 and the secondhand Bailie Nicol Jarvie operated a packet service, on which a "good number of Passengers had a delightful trip listening to the band provided, enjoying the hospitality…and inhaling the sea-air". Traffic with Liverpool was especially targeted, and in 1833 an additional berth was built for the Carlisle & Annan’s vessels, travelling to Liverpool via Annan; in 1839 a regular passenger service to Annan itself was also started.

But by the 1840s both port and canal were in trouble, for although the railway across Shap had not yet been built, combined rail/sea journeys were possible via ports such as Whitehaven. By 1852 the canal’s finances were in such straits that the committee decided to convert itself into a railway. The Carlisle Canal Company became the Port Carlisle Dock & Railway, and by the time its authorisation Act had been passed, in August 1853, the canal was already being drained. Within a year a single track railway had been laid, mostly along the route of the old canal, the level gradient only interrupted at intervals by mysterious ‘ups and downs’ where the locks had previously existed. Steamer services were restarted between Port Carlisle and Liverpool and a pleasure ground was laid out at Port Carlisle to distract the waiting passengers. The company initially hired in carriages and locomotives, but in 1855 it was confident enough to buy an engine of its own.

By then various factors, not least the serious silting which impeded the steamships, had cast a shadow over the future of Port Carlisle, and in 1854 a Bill was put forward for a railway to a more convenient port at Silloth, the new company being the Carlisle & Silloth Bay Railway & Dock. This was inevitably attacked by many – it was impossible to refute the claim that Port Carlisle would become a white elephant once Silloth’s dock was opened – but the Act was quickly passed and work went ahead on building the new line, which branched from the Port Carlisle line at Drumburgh. A Committee was established to operate both lines, and in August 1856 the 13 mile Silloth line, over easy terrain, was opened, with the Liverpool steamships transferred there, a jetty having been constructed. Traffic on the Port Carlisle line now fell so low that the Committee decided to dispense with its locomotive – which doubtless found better use on the Silloth route – and employ a horse. From 1859 this hauled a coach called Dandy No.1, with compartments for 1st and 2nd Class passengers, and an outside seat for the 3rd Class; luggage, as on a stage coach, travelled on the roof. On the rare occasions when there were too many passengers for the coach the luckless horse would have to return for them later. This system survived until 1914, when the line was ‘modernised’ for steam working. The last passenger train ran in 1932. Today Port Carlisle is a fascinating relic of a failed project. Parts of both the station platform and the canal lock survive, with a mysterious brick jetty wall (complete with steps to nowhere) across what was once a harbour. The houses line one side of the single street, almost exactly as on our map, with a couple of cross streets to a parallel road behind, hinting at the adoption of a grid plan for the projected town – and that really is it.

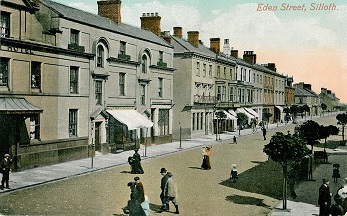

The railway to Silloth opened in August 1856 and from the outset the directors had decided to develop the town as a resort, a "sea bathing place for the inhabitants of Carlisle". 46 acres of Blitterlees Common were acquired and already by 1857 a grid pattern of streets was being laid out over what had previously been dunes and open fields. "The great Sahara of Silloth is fast losing every feature which characterised its former self", wrote a local journalist, "the sandhills are giving way to green sward…and the buildings have assumed a regularity and completeness worthy of the name of a town”. Terraces, hotels, baths, bathing machines, boarding houses, all the usual trappings of a resort were quickly established, and by 1861 another 160 acres of the Common were being purchased. In 1860 the Silloth Gazette was able to boast of four hotels: the Queen’s and the Solway (today the Golf) were in prime positions on Criffel Street, overlooking The Green which separated the town from the sea, and on which a cluster of pine trees would eventually provide relaxing walks; a later directory described the two hotels as "replete with every comfort…both are near the golf links, and have good billiard rooms, tennis grounds and livery stables". The plots shown here opposite the Queen’s largely comprised tennis courts. The less prestigious Royal and Albion were set back along Eden Street and there were also 38 lodging houses. So enthusiastic were the directors that they spent £6,000 on clearing sandhills to improve the view. Nor had the original intention of the venture been forgot, for in 1859 the Marshall Dock – named after one of the promoters, William Marshall, MP for East Cumberland – was opened, within which shipping could be protected by two pairs of gates, the inner for everyday use, the outer for added protection from storms or unusual tides. A twice weekly steamship service to Liverpool was on offer, and within 10 years there were regular sailings to Douglas, Dublin and Whitehaven as well as up the Solway to Annan and Dumfries.

No seaside resort could be complete without its baths, and these were provided across The Green, with "one hundred thousand gallons of fresh sea-water pumped up by steam power at every tide". The baths themselves were in the basement of the building, with a cafe on the ground floor. By the 1880s the baths, where hot or cold sea-water could be had "on short notice at reasonable charges" were under the "energetic management of Mr and Mrs Bell", and they remained with that family until Mr Bell’s death in 1920. There was then a dispute between Holme Cultram Urban District Council and local ratepayers as to the future of the building, the latter inevitably opposing the expense of municipal ownership. The dispute – the ‘Battle of the Baths’ – led to several votes, each duly declared invalid, until a secret ballot led to the purchase being defeated by 260 votes to 202. The building later became an amusement arcade, and retains that purpose today. The baths were about as frivolous as Silloth got, although there were the usual complaints of illicit mixed bathing down on the beach. So safe was the resort considered that on Carlisle race days hundreds of the city’s schoolchildren were packed on the trains to the coast, here to escape the temptations of the Turf.

Silloth’s early growth was short and sweet, and by 1861 the railway company was forced to seek extra capital. The following year the North British Railway, which had just opened its ‘Waverley Route’ to Carlisle, leased both the Silloth and Port Carlisle lines, purchased its own ships and even opened an office in Dublin. The Silloth-Dublin passenger service was not a success, though the route to Liverpool proved more enduring; however, a good range of freight services were developed, including cattle from Ireland, phosphate from South Carolina, and wheat from various ports in North America and the Continent. Exports included coal, manure and burnt ore. One ship returning from Newry brought granite as a ballast cargo, for use on Silloth’s church, built on land donated by the railway company; Christ Church, centrally sited on Criffel Street, was built in 1870 and a tower and spire added in 1878. The usual nonconformist chapels were also built in rapid succession: the Congregational Chapel first in 1862, followed by a Wesleyan chapel in 1875 – "roomy, and furnished throughout in pitchpine" – and a Primitive Methodist chapel in 1877 – "a good brick building, relieved by stone dressings, and of plain Gothic style". Surprisingly, in view of what was now a distinct Scottish influence, the Presbyterians had to make do with the Oddfellows’ Hall, before eventually building a chapel in Caldew Street.

The health-giving reputation of the ozone soon led to invalids coming here for convalescence, if not actual cure, and in 1862 "a number of medical men and generous citizens" established the Cumberland & Westmorland Convalescent Institution on dunes south of the harbour. This was intended for "the artisan class" or "poor persons" who were recovering from fever, and was so successful that it was expanded across the years, a children’s ward being added in 1882. The Institution, which could accommodate over a hundred patients, with all the wards on the ground floor, is still in use today. A short railway branch already existed in 1860 through the dunes to the Leesbank Salt Works, just south of this map on Blitterlees Bank, and a siding was run from this to the Institution.

The health-giving reputation of the ozone soon led to invalids coming here for convalescence, if not actual cure, and in 1862 "a number of medical men and generous citizens" established the Cumberland & Westmorland Convalescent Institution on dunes south of the harbour. This was intended for "the artisan class" or "poor persons" who were recovering from fever, and was so successful that it was expanded across the years, a children’s ward being added in 1882. The Institution, which could accommodate over a hundred patients, with all the wards on the ground floor, is still in use today. A short railway branch already existed in 1860 through the dunes to the Leesbank Salt Works, just south of this map on Blitterlees Bank, and a siding was run from this to the Institution.

Even in the early 20th century the health-giving properties of the ozone were being proclaimed, and mysterious statistics were produced suggesting that Silloth had 8.4 of it, whereas poor old Torquay had a mere 4.6, although nobody explained exactly what they meant. By then, of course, any self respecting health resort needed its ‘Hydro’, and one was duly opened in 1908 on the terrace south of the Queen’s Hotel. This establishment, which seems to have been one of the first to refer to the resort as ‘Silloth-on-Solway’, boasted a true panoply of baths – Turkish, Russian, Sulphur, Pine, Peat, Ammonic, Mustard, Seaweed and others – with treatments ranging from acetopathy, osteopathy, electric sun-ray and chiropody, to the less appealing bowel douche and ‘piles rising spray’. Apart from the many tennis courts there were golf links, bowling greens and, of course, sea-bathing for the more active – although cricket had earlier been banned, the hard ball apparently presenting too much danger to passers-by. So assured was the town’s reputation by 1929 that only a lack of accommodation for his large entourage prevented George V coming here for his convalescence rather than Bognor.

Meanwhile disaster had struck the Marshall Dock, for in 1879 the west side of the wall by the dock entrance had suddenly collapsed, dislodging one of the gates and so allowing the water to escape. Within minutes 21 ships and boats – including the steamship Silloth – were stranded in what had become a dry dock, and the dock entrance was blocked by debris. It was almost a fortnight before the imprisoned vessels could be released. Rather than repair the gates, it was decided to reopen the Marshall Dock merely as a tidal dock – the map clearly shows that silt was allowed to build up by the harbour walls – and build a slightly larger, six-acre New Dock further inland, entered through the old dock. Work on the new dock, which was built to take ships of 2,000 tons burthen, started in 1882 and it opened for shipping in 1885, the first vessel to enter being, appropriately enough, the Silloth. The digging of the dock, of course, produced vast quantities of soil and much of this was used to landscape The Green, where pine trees were planted for the Queen’s Golden Jubilee in 1887, and to create the golf course, opened in 1892.

A 1,000 ft wooden pier, though built primarily as an aid to shipping – see the mooring posts – enticed promenaders out over the Solway, especially for the town’s famous sunsets. There was a lighthouse at the end of the pier, and ships’ captains navigated up the Silloth channel by aligning this with an onshore lighthouse, the East Cote Light, just north of our map. Another light – ‘Tommy Legs’, named after one of its keepers, Tommy Geddes – warned ships of the Lees Scar rocks out in the Solway. However, the pier was badly damaged in a storm in 1907, and by fire in 1942, these incidents depriving it of about 200 ft; much of the rest collapsed in 1959 and the stump was demolished in the 1970s.

In 1886 a flour mill was opened at the side of the dock by Henry Carr. A bakery had been founded in Carlisle by Jonathan Hodgson Carr in 1831 and this had grown to include flour milling. In 1904 the Silloth mill was greatly enlarged and modernised, as the New Solway Flour Mill. Following a financial crisis soon afterwards, the chairman, Theodore Carr, turned the family business into a public company, split into three groups, Carr & Co, C.F.M. and Carlisle Bread & Flour Co. The bakery became part of United Biscuits in 1972, and the flour mills are owned by Carr’s Milling Industries plc. The flour mill quickly became the town’s principal employer, and continues to be a dominant presence today. A major feature of the new mill was a ‘Carel’ steam engine, which drove a 21 ton, 18ft 6in diameter flywheel; this was built in Belgium and shipped direct from Ghent to Silloth in 1905. This worked round the clock, getting through 11 tons of coal a day and producing the power for almost 200 tons of flour a day; the massive flywheel is said to have worked continuously through both world wars. The steam engine and flywheel were mothballed in the 1970s but have since been renovated and preserved as the main exhibits in a private museum established within the mill.

In the 1930s a new bank manager, Bert Wilson, came to Silloth, living in a flat above the District Bank on Eden Street. His wife, a musician who had already won piano competitions, joined the local amateur dramatic society and gave piano lessons to children. Soon after moving to the town she was asked to accompany the Silloth Choral Society, and as a singer she is then said to have made her first solo performance in a concert, held by the society, at the Pavilion. She was, of course, Kathleen Ferrier, one of the greatest and perhaps the best loved of all English singers, and a competition in Carlisle would soon propel her away from Silloth and to international fame.

The Pavilion shown here, as today, was a delightful little building, mildly Oriental in character, perhaps the size of a large bandstand and raised up above the green. In the 1930s the UDC took this over and converted it "into a first-class entertainment hall with 640 tip-up seats…the finest Concert Hall on the Cumberland Coast…The Rendezvous of the Elite", the publicity went on, with a "Grand Balcony [offering] an excellent view of the Galloway Mountains and Solway Firth". There were regular shows here, both matinees and evening performances, throughout the summer. The building at the corner of Station Road and Lawn Terrace, once the town’s Assembly Rooms, had become "the Premier and Senior Cafe in Silloth"; today it is a fish and chips cafe, though its main room cries out to be a dance floor once again.

At one time Silloth had boasted more lodging houses than Windermere, but after the 2nd World War its glory days as a resort began to fade away. Its transport links with the south had always been precarious (though there was a branch from Abbey Junction on the Silloth line to Brayton, on the Maryport & Carlisle, a journey from Silloth to Maryport by train was timetabled at 6 hours 28 minutes in 1918) and the NBR had quickly lost interest; in 1923 it became an outpost of the LNER. Into the 1930s a regular twice-weekly steam ship made the journey from Silloth to Dublin via Douglas, generally operated by the Yarrow, built for the route in the 1890s. However she was operated by an Irish company, and so unable to operate a reliable service during the war, when the port was busy with freight for the war effort – and when the Yarrow was regarded as an alien vessel. Regular passenger services never recovered, and this played a part in the decline of the railway line, leading to its closure in 1964.

Silloth today has changed remarkably little from the modest resort shown on this map, the departure of the railway (the station building has just been demolished at the time of writing) and the loss of the pier the major changes. The port, now owned by Associated British Ports, still sees regular shipping and recently boasted its largest ever cargo, 3,420 tons of fertiliser brought in by the Antari for Carrs Fertilisers. The schools on Liddel Street now house the Tourist Information Centre, with space for displays. Silloth’s gentle charms, its golf, sunsets and easy walks, are treasured by those who venture out onto the Solway coast, though the sea itself is strangely bereft of pleasure craft (can nobody revive the Silloth-Annan run?). Several of the main streets retain their cobbles – apparently these are now listed – and the Golf, nee Solway Hotel, still has a decent snooker table in its basement. It is a town well worth visiting.

©Alan Godfrey, October 2007

Principal sources: Mary Scott-Parker’s Silloth (Bookcase, 2nd Ed 1999) is a readable history of the town, much more than the ‘nostalgic scrap book’ the author claims for it, and is recommended. Other sources include Bulmer’s History & Directory of Cumberland 1901; Charles Hadfield & Gordon Biddle, The Canals of North West England, Vol 2 (David & Charles 1970); the Official Guide to Silloth on Solway (1930s, reprinted by Silloth Tourism Action Group).